A Look Back and a Leap Forward: 30 Years of Automated Parking

My journey into the world of mechanical and automated parking began in the mid-90s, when a developer named Patrick Kennedy sought ways to develop boutique, multifamily residential projects in Berkely, California. In order to achieve his pro forma, he needed to add more units, and subsequently more parking, to a space-constrained site. The only way to make it happen was with simple stacker mechanical lifts that allowed him to densify parking by taking advantage of volume.

Finding the right balance between parking and costs is often the stumbling block for projects like this. Innovative ideas that can take that pressure off are important to clients, so I began reading about mechanical and automated systems, visiting sites that had implemented them and talking to developers. When should these systems be implemented? Why? How do we determine the right system? Is a valet always necessary, or can they be user-operated? What are the upfront costs versus ongoing maintenance?

What I learned was that these solutions can take advantage of volume to increase efficiency in ways traditional parking design can’t, which can have a significant impact on the bottom-line budget for projects with a lot of vertical height. This was the kind of ingenuity we needed to integrate into the US market.

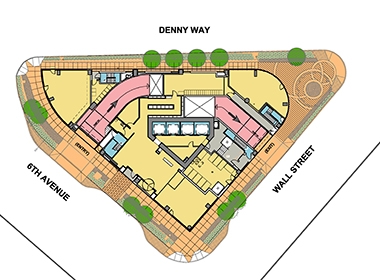

Site plan for The Spire in Seattle

Site plan for The Spire in Seattle

About 15 years ago, I began working with Paul Menzies, who was developing a residential tower in Seattle that came to be known as The Spire. This unique project featured a triangular shaped site, which was a no simple design task to begin with, but when it came to parking, things got even more complicated.

In order to provide the views Paul envisioned, the tower’s structural core needed to be in the center of the building. This sliced the available area to design the parking into 30 foot wide sections. Since conventional parking requires 60 feet, it wasn’t an option. However, an automated system seemed like a natural fit.

To find the right solution, we needed more answers. Paul and I looked at systems on two continents. First, we visited Italy and Switzerland. Later, China and Taiwan. We saw mechanical and automated systems integrated into downtown cores, retail areas and residential areas in which homeowners built garages and sold stalls to their neighbors in a unique, shared parking approach. Gas stations and other amenities were seamlessly added to create convenience. The level of adoption of these systems by the general public was inspiring, and opened up entirely new possibilities for parking design in urban US areas.

As a member of the National Parking Association’s Parking Consultant’s Council, we track metrics such as increasing car sizes in the US and the impact on stall geometrics. As cars get bigger, the square footage required to efficiently park the same number of cars grows with it. The size of a parking stall is also not simply the size of a typical car. Doors have to be able to open and close, and people have to be able to get out and move safely through the structure.

Transfer cabin at The Spire

Transfer cabin at The Spire

However, when employing mechanical and automated systems, that space can be significantly reduced. Valet-operated systems don’t require as much maneuverable space as clients.

In a fully-automated parking system, the user gets in and out of the car in one place – a transfer cabin – which means the actual parking system can eliminate space needed to for humans. Once delivered to the transfer cabin, not only is no one entering or exiting the car, but the car is never even started within the system, which is a green feature.

Factory visits were also part of my fact-finding trips with Paul. Understanding the attention to detail required for a successful system put things in perspective: the more a manufacturer can control all the components of their system, the better the end product in terms of performance, maintenance and minimal downtimes.

For The Spire, we considered puzzle, cantilevered, shuttle, post and no-post systems to ensure the right solution not only met the needs of the site, but also provided the desired experience for residents and the best long-term value for the project. Ultimately, the exploration resulted in better parking design for the now-open luxury residential development.

The Spire is one of hundreds of projects benefiting from this approach. While it was slow to catch on initially, in the past five years I’ve seen a significant jump in projects studying and implementing mechanical and automated solutions in the US. Integral to the decision-making process is understanding the needs of your user base and how the parking system fits into the big picture. For example, what level of service will your target customer expect? What are your expectations on retrieval times? What is the backup plan for unexpected down times? What will ongoing operations, maintenance and repair costs look like?

Upfront costs are another significant consideration. A valet-parked mechanical stacker may be the cheapest option to purchase and install, however the costs of operations are often higher in the long run. A semi-automated puzzle system may cost twice as much, but because it offers independent access, the operation costs can be significantly lower. While a fully automated parking system is often the most expensive option – depending on size and scale – it can offer the highest level of service and ease of use. To learn more about different system classifications and other considerations for mechanical and automated parking, click here.

Automated parking system at Fred Hutch Cancer Center in Seattle

Automated parking system at Fred Hutch Cancer Center in Seattle

While residential use is the most popular, we have also designed these systems for other types of developments. For example, the Fred Hutch Cancer Center in Seattle recently opened a fully automated parking structure that allows patients to drop their vehicle off with a valet and continue on to their appointment with minimal stress. A valet then drives the vehicle into the automated system via a transfer cabin, which selects an open spot and stores the car until it is needed again.

Office campuses are beginning to utilize these options as well. In addition to densifying parking in new projects, they can also aid in redeveloping an existing campus. For instance, an office campus redevelopment project in El Segundo, California added valet-operated mechanical stackers to an on-grade lot to densify without the expense of structured parking. A complex mixed-use project in Menlo Park that serves office, residential and retail patrons turned to a self-park puzzle system to accommodate high rates of turnover for retail visitors and the steadier stream of office users.

One of the biggest challenges to overcome when designing and integrating these systems is education. A significant part of my journey has been not only educating owners and developers to help them understand what’s out there and how it could benefit them, but also coordinating with the design team and meeting with city planners. The design team needs to understand how these unique systems fit into the overall design of a project, including complex construction phasing. As city codes often focus on criteria and dimensions, it’s vital to educate city planners on how this approach differs from a traditional parking facility, and how codes can be updated to accommodate them.

Once everyone is on the same page and the project is completed, you then have to educate the userbase who will be parking in the facility. Mechanical and automated parking systems are new and different, and public perception tends to be wary. Ensuring their experience is positive and stress-free paves the way for greater adoption.

This exciting technology is evolving at a breakneck pace. The ability to automate EV charging as part of these solutions is one of the latest emerging innovations, which will help future-proof these facilities as adoption of EVs continues to increase.

Every project is unique, and finding the right solution for each one makes me feel like a matchmaker: who fits with what, and why is it a good fit? Nearly 30 years and hundreds of projects since that first residential development in Berkeley, my goal is to continue educating owners and developers on how mechanical and automated parking can help them achieve their project goals.